So it seems the gun world is up in arms (that’s right, I went there) about the fact that the Spearmint Rhino chain of strip clubs has sued gun manufacturer Chiappa Firearms for using a confusingly similar mark on its RHINO 40DS model .357 magnum (Spearmint Rhino Companies Worldwide Inc. v. Chiappa Firearms Ltd et al., 2:11-cv-05682-R–MAN, Central District of California). I’ve seen no comment from the strip club community. Apparently they have what they regard as better things to focus on.

Let me mention at the outset that a good friend and eminent member of the Michigan bar tipped me off to this, uh, tussle. I appreciate it very much because a) it provides a great opportunity to talk about an enduring public misconception about trademark infringement, and b) nothing drives traffic to a blog like the phrase “strip club” in a post title.

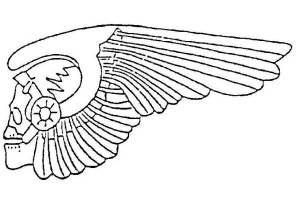

Here’s a good photo showing a comparison of the marks, courtesy of this article on the GUNS.COM site. (I couldn’t help smiling at the phrase “PLENTY of VIDEO” in the title – another savvy web marketer at work. Touche, my friend.)

I don’t think it’s unreasonable to observe that, aside from the rhinos facing in different directions, the marks actually do look quite similar. Spearmint Rhino has registered its rhino-outline-in-a-circle mark for “T-shirts and hats; lingerie, namely panties, g-strings, brassieres and corsets for semi-nude and erotic dancers; golf clothing, namely golf shirts, jackets, vests and caps.” Chiappa has registered its rhino-outline-in-a-circle mark for firearms, but not clothing.

If you clicked over to the GUNS.COM article (and I hope you did), you’ll notice that both the article itself and the reader comments express some surprise and doubt that Spearmint Rhino’s suit has any merit. I believe the phrase “snowball’s chance in hell” shows up prominently. This line of thinking can perhaps be summed up as: no one would ever confuse pistols for panties. Or maybe: how can you mix up guns and G-strings? Or how about: one holds bullets, the other holds boobs – case closed! (Sorry. Traffic, you understand.)

So, would anyone really go out to buy a gun and come home with a G-string instead? Okay, I’ll grant that one can imagine situations where that might happen. But would it happen because of confusion caused by the trademarks involved?

The answer to that question is, probably not – but it doesn’t matter. This is where the enduring public misperception comes into play. Trademark infringement is not limited to situations where customers are confused into buying one party’s product thinking they’re buying another’s. This is the important take-away from this article.

People often don’t realize that trademark infringement also exists when the nature of the marks and goods could cause the public to believe there is some connection (such as license, for instance) between the two companies, when in fact that connection doesn’t exist. Again, not the undies. This is the important part.

Looked at in that light, maybe Spearmint Rhino’s legal claims don’t seem so ridiculous after all.

First of all, while the frilly underwear may be more fun to focus on, hopefully you noticed that Spearmint Rhino’s trademark registration also covers T-shirts, hats, golf shirts, jackets, vests and caps. It’s not unusual at all for makers of outdoor lifestyle products to use their marks on that kind of clothing.

– The famous GLOCK gun trademark is registered for firearms, but also for “clothing, namely, footwear; headgear, namely, caps, baseball caps, earmuffs, headbands, and headcloths; T-shirts; polo shirts; fleece sweaters; wind-resistant jackets; track suits; neckerchiefs; neckties.” Perhaps it bears mentioning that T-shirts (at least the white ones) are also a type of underwear?

– The famous REMINGTON mark is registered for guns, but also for similar clothing goods.

– Heck, for that matter, the famous HARLEY-DAVIDSON MOTOR CYCLES trademark is registered for motorcycles, but also for hats and caps, and even for “T-Shirts, Tank Tops, Halters, [and] Panties.”

Second, how are these kinds of lifestyle trademarks commonly used on clothing? By licensing the trademark to another company that’s already in the clothing business. For some reason, people who spend all day boring out gun barrels don’t want to spend their evenings with straight pins in their mouths, basting seams.

So, when we strip away (sorry) all the rhetoric, what do we have here? Two marks that are pretty darn similar in appearance. One is used on guns, and one is used on a line of products that often have famous gun trademarks on them, via trademark license.

Could anyone see the Spearmint Rhino mark on, say, a baseball cap and mistakenly believe that the mark was licensed by the gun maker Chiappa? You can draw your own conclusions, but hopefully I’ve given you a better legal framework to think the matter through.