Someone didn’t do their homework, and it’s going to be a costly and embarrassing lesson.

The Hells Angels Motorcycle Club has sued the Alexander McQueen fashion house for trademark infringement. The suit was filed October 25, 2010 in U.S. District Court in Los Angeles. The club also named the Saks retail chain and Internet retailer Zappos.com as defendants for their roles in selling the allegedly infringing products.

In its complaint, the Hells Angels club requests findings that the defendants infringed its trademarks and committed unfair competition and trademark dilution. The club seeks an injunction preventing additional sales of the alleged infringing products as well as a recall of the alleged infringing inventory. The Hells Angels ask that the inventory be delivered to a third party for destruction. Finally, the club seeks money damages which it asks be multiplied because of the blatant and “exemplary” nature of the infringement, along with the club’s attorney fees for the action.

The alleged infringing "Hell's Knuckle Duster" Clutch marketed by Alexander McQueen Trading Limited.

The motorcycle club claims that Alexander McQueen Trading Limited, the fashion house founded by designer Alexander McQueen (who committed suicide earlier this year), infringed its winged skull design mark by using it in a multi-finger “Hell’s Four Finger” ring and “Hell’s Knuckle Duster” clutch handbag (see pictures.) The suit also claims that the defendants infringed by marketing a jacquard dress and a pashmina scarf using the word mark HELLS ANGELS, without authorization by the club.

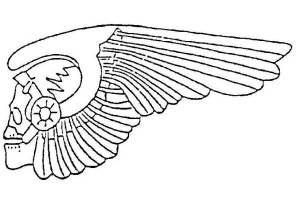

The Hells Angels club registered a winged skull design (which the club calls the “HAMC Death Head design”) in 2009 as U.S. Trademark Registration No. 3666916 for goods including “jewelry, jewelry pins, clocks and watches, earrings, key rings made of precious metal, badges made of precious metal, and chains made of precious metal.” An image of the registered design appears at right, below. In its complaint, the club claims use of the design since 1948.

An image of the "HAMC Death Head design" mark registered for various goods, including jewelry, by the Hells Angels Motorcycle Club.

The same design is registered separately (U.S. Reg. No. 3311550, issued in 2007) for “clocks; pins being jewelry; rings being jewelry.” In that registration the Hells Angels claim use of the mark on those goods since 1966.

What Happened Here?

This is, by all appearances, a tremendous blunder by Alexander McQueen Trading Limited, as well as Saks and Zappos.com. You’re welcome to judge for yourself, of course, but to this observer the designs used by the defendants unquestionably are confusingly similar with the design registered by the Hells Angels. The use of the words “HELL’S” and “HELL’S ANGELS” merely completed the effect, making it a virtual certainty that consumers would perceive some connection with the infamous motorcycle club.

Here, boys and girls, we have a perfect example of why marketers should always consult an experienced trademark practitioner well in advance of introducing a new product line. It frankly seems hard to believe that marketers as savvy as those at the House of McQueen, Saks and Zappos.com could have failed to recognize the potential trademark implications of their actions here. Perhaps they did.

In any event, it’s highly unlikely that these product ideas would have survived a review by an attorney experienced in trademark law. Right about now, it probably seems to the good people at the House of McQueen, Saks and Zappos that a review by their trademark attorneys would have been money well spent.

RING AND HANDBAG IMAGES COURTESY OF STYLITE.COM.